Appeared at the 2025 Bay Area Maker Faire

The booth staff

Crafty and I wrote our respective proposals and both of us got in, so thanks to the combined booth staff of Crafty, Lindsay, and Zipp.

Love, loss, and shiny silvery spandex

Most of my projects end up having a weird story about love, loss, shiny silvery spandex, and unrequited dreams.

We can start with the very bad and very forgettable 1986 movie SpaceCamp. Made before the Challenger disaster where a SRB failure caused a loss of crew and vehicle, it features a SRB failure that caused some kids in Space Camp and their instructor to get launched into space. Obviously, it complicated things to have a release date after the disaster.

I can’t watch it these days because it’s too much cringe, but I love certain bits of it. One bit was the Space Station Daedalus scene where they frantically try to grab an oxygen tank from the in-construction space station except that the camp instructor is too big to fit between the beams so they grab the kid, who spends most of the movie being super-cringe and stick him in a space suit because he’s small enough. They break a wide variety of laws of physics, spacecraft design, operational planning, flight safety, and so on for a plot that was, to be fair, really mediocre.

Still, because the kid was cringe and I was cringe and when I was a kid I would usually identify with the cringe socially awkward nerd character even though most of them coughWesley Crushercough were written very poorly (no shade on Wil Wheaton, of course — Wil’s great) so I kinda still wanted to be one of the kids trapped on a space shuttle. Because (Lego Movie Space Guy Voice) SPACCEESSHIIIIIP!

Yeah, OK, maybe wanting to be on a spacecraft that you don’t actually know how to fly with questionable chances of survival isn’t a great fantasy.

Why a truss?

The eighties featured a lot of trusses. In buildings, they became one of the trademarks of the late modernist architecture period, representing “cool” and making the prior brutalist or streamlined or art deco or merely modern buildings look dated. In space, they represented a turning point of dreams where the Space Station Freedom then ISS had a truss structure in contrast to prior stations that were mostly made of docked cylinders. In science fiction, starting in the 1980s, trusses became something fun and vaguely futuristic one could throw into the background.

I wanted to make illuminated sculptures, but I only have so much room to work with. Thus, I asked myself “How would I make something that looks neat but fits into a ziploc bag?” A lot of my inspirations seemed to be mostly air anyways, so this didn’t feel impossible.

Around the same time, I’d been browsing through the NASA Tech Report Server to look at the wealth of papers from the 1980s. I realized that the classic concept art renditions of space stations that were based on trusses like the fictitious space station in Space Camp or the dual-keel proposal for Space Station Freedom was only really scratching the surface of NASA’s ambitions to build giant structures in orbit, all using trusses and with great consideration to the size and weight of the structure.

Unfortunately, the flights that really started to test these truss systems in space happened right before the Challenger accident, after which having astronauts assembling giant satellites stopped sounding practical, thus the research slowed to a trickle and didn’t attract any attention until 10 years ago where everybody looked at how amazingly difficult it was to get JWST deployed and wondered if maybe the solution for the next generation of large space telescopes was robotically assembled trusses.

While I’d been poking at CAD models for trusses for a long long time, seeing all of the interesting structural bits that NASA had been working on, trying to understand the artistic applications of something that was primarily oriented towards a butterfly-light radio antenna or telescope or space station backbone gave me a lot to think about.

I guess even outside of making light art or space station trusses, I just like the idea of large things that can be printed on a standard-sized 3D printer.

Thus, truss systems seemed to be a really good idea to make illuminated structures that would fit into a ziploc bag.

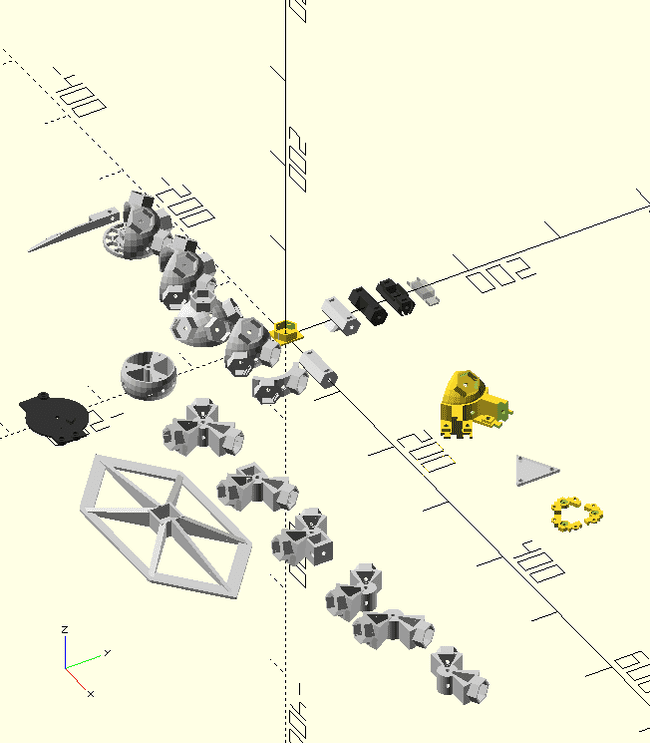

The structures

Amusingly, the first truss is exactly the truss from Space Camp.

The first structure is generally the “octet” truss from Buckminster Fuller, constructed out of regular octahedra and regular tetrahedra in a 1:2 ratio.

From there, you can remove most of the joints, rotate the structure on the side, curve it slightly and build a hex-wall.

The parts are interchangeable between the two structures.

The library

NASA’s 1980s truss papers were based on this core assumption that they needed to figure out how to make space construction much cheaper, to make it easier for there to be enough reasonably priced missions doing amazing things to fill up a shuttle every week or so.

Thus, there was this idea that you’d build one… or, if not one, a small number … of truss systems.

I wrote SpaceframeSCAD, a tool to build parametrically defined pieces to build a variety of structures. And, it works in much the same way. There’s a bunch of parameters to set like the desired screw size, nut type, node radius, and strut length.

And then most of the pieces have their own set of parameters, such that you can construct a variety of related structures.

I would really really hate to try and draft all of the individual part variants in a regular CAD tool.

The printers

I’ve got a 300mm x 300mm Voron Trident.

However, it turns out that the optimum size for this still fits, albeit barely, on the standard Ender 3/Prusa i3 bed. The standard test piece to measure how good bed adhesion is for a given combination of materials, temperature, bed, and bed adhesion promoter is to print a long narrow beam… which is basically what the struts are.

A friend helped me out by printing some stuff at the makerspace she’s got access to while I was away for a week and the makerspace decided that they didn’t want to deal with gluestick or other adhesion promoters, so they use a completely clean satin PEI sheet and things didn’t stick as well as my textured PEI sheet with purple gluestick… so that didn’t work quite as well as one might have thought.

The 300x300mm bed still makes my life easier because 250mm is diagonal on a Ender/Prusa bed whereas I can just print a row of them on my printer.

Tariffs and the end of the de minimis made life difficult because I have a particular hotend on my Trident that is well regarded by the Voron community but for the longest time, only available directly from the manufacturer, so I was actively concerned about running out of spare bits until it finally showed up at a US-based merchant’s store.

The side quest

Tomatoes are dangerous.

”Dangerous?” you ask. “Why are tomatoes dangerous?”

And, as always my reply is “Well, if they weren’t dangerous, why do we put them in cages?”

My best-friend-besides-my-spouse likes to plant things in my patio. Tomatoes are a good thing to grow because they go great in salads so they get used up and store-bought tomatoes are usually sad gene-tampered hybridized not-actually-ripe fake products. And tomatoes, being dangerous, need to be caged.

My desired patio garden aesthetic is less cottagecore and more “Looks like a fancy spaceship arboretum or domed-habitat garden from Star Trek TNG” and so normal tomato cages just aren’t going to do it for me.

Thus, not only is this useful for making illuminated artwork that fits in a ziploc, it’s also part of my garden.

The math and how LLM’s did not help

In spite of having a BS in Math and Computer Science and doing a bunch of computer graphics, there’s this whole world of polytrope geometry that … I had to figure out myself the hard way.

I’m not sure if this level of geometry was actually even something that was offered for me without requiring me to get a higher degree or make more room for the right geometry classes?

This is one of my test cases for LLM’s because it’s rare enough in the set of scrapable content. OpenSCAD code generation is very hit-or-miss in general because it’s got a small sample set. And the amount of OpenSCAD code to scrape that actually solves the problem is almost non-existent. Likewise, the math, especially the important parts of the math, doesn’t seem to be evident enough for the AI searchers to crank it out.

Obviously if someone cooks up AGI, real AGI, it would be able to fill in the gaps.

Anyway, I’m not sure if my library is ever going up anywhere, if you drop me a line, I’ll talk your ear off.

The electronics

At Maker Faire 2024, we had some demo bracelets that used Molex MicroFit 3.0 connectors that I’d crimped my self with an iWiss SN-01BM to link them to the power supply. A whole lot of people fiddled with them, forgot that they were wired down and yanked at them, et al and the Molex MicroFit 3.0 connectors survived the experience quite well, therefore I’ve made that the standard for LED wiring for my projects.

Tariffs and the end of the de minimis made life difficult for this part of the project, too.

There are some PCB fabrication services that are based on the US. Traditionally they focused on only the highest-end markets: the people who had to fab their products in the US like defense contractors or people who needed a rapid turnaround. There are a few companies that have started trying to hit this marketplace, but it’s still awfully expensive.

In a rush to use up the TTGo T7 ESP32 boards that I had a set of while PCB fabrication was more reasonable priced, I designed the gen3tr1ss board as part of the last order before the de minimis went away and tariffs hit. The goal was to use my new standard connectors and be useful for larger wired projects like home automation and the truss thing I’d been wanting to do.

I normally put puns on my silkscreens but I was in a real rush so the silkscreen doesn’t have any.

The LED strips

Tariffs also got in the way here.

Most of the time, if you look for a thing, you will find some no-name merchant selling a version thereof on Amazon and sometimes even the same merchant will have a store on AliExpress. For example, the BTF-Lighting strips that are well regarded. There’s a store on both sites.

Over the years, most people doing LED stuff have mostly moved over to shopping at AliExpress, thus there’s a bunch of stuff that’s only available there.

Like the COB strips I’m using, which are part of what BTF-Lighting sells only on AliExpress. Thankfully AliExpress moved quickly to set up duty-paid shipping. I ended up using their WS2812 COB strips that have 160 LEDs/M. They were less expensive and less LEDs overall than the fancier denser COB strips but were fine enough for the pixels to disappear behind the diffusers.

In order to make things work, I needed to take the 5M spool of COB LEDs, cut it into strips of a specific length and then solder pigtails on each end. That’s … quite a lot of work. The last few weeks before the Maker Faire were a little bit exciting because I wasn’t sure if I was going to get everything crimped and soldered and everything in time.

Power supply

I replicated, more or less, the power supply wiring of my Voron Zero, except using a 5v Mean Well supply and then used Wagos and some wiring harnesses to power the works.

DMX Control

In order to have a series of interesting effects, I put WLED on the ESP32’s and used QLC+ to program the show. I ended up running in Effects Segment mode, where the local WLED instance is mostly in control and the QLC+ controller

I ended up getting myself a GL.iNet Slate 7 travel router to set up a private network and borrowed a Windows laptop to run QLC+ on because I was running out of time and didn’t get around to setting up a headless pi to run QLC+. Probably next time, I’ll set up a headless pi.