I always wanted to build a 6502 based computer.

The 6502 is the chip used in all sorts of computers throughout history, ranging from the Apple II, the NES, and the Commodore 64… all of the way through to the Terminator and Bender.

I’ve drawn a bunch of attempted schematics, never really bothered to build any of them.

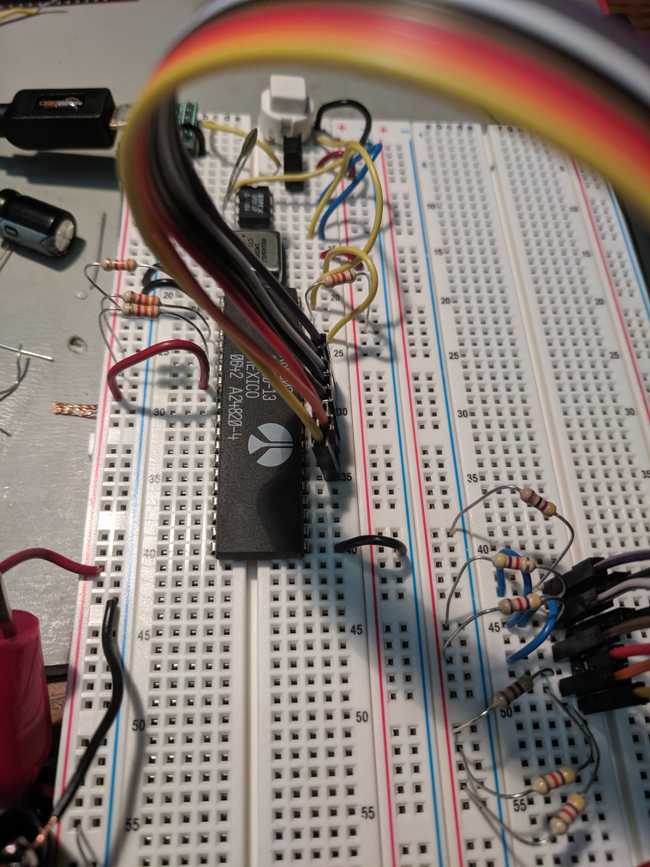

I’ve had the requisite chips sitting around since 2008 or so.

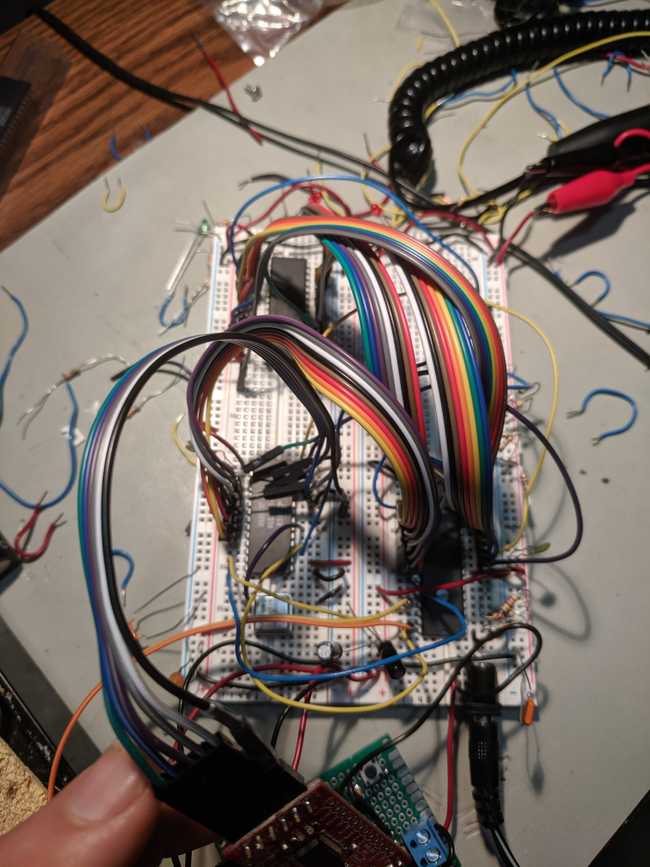

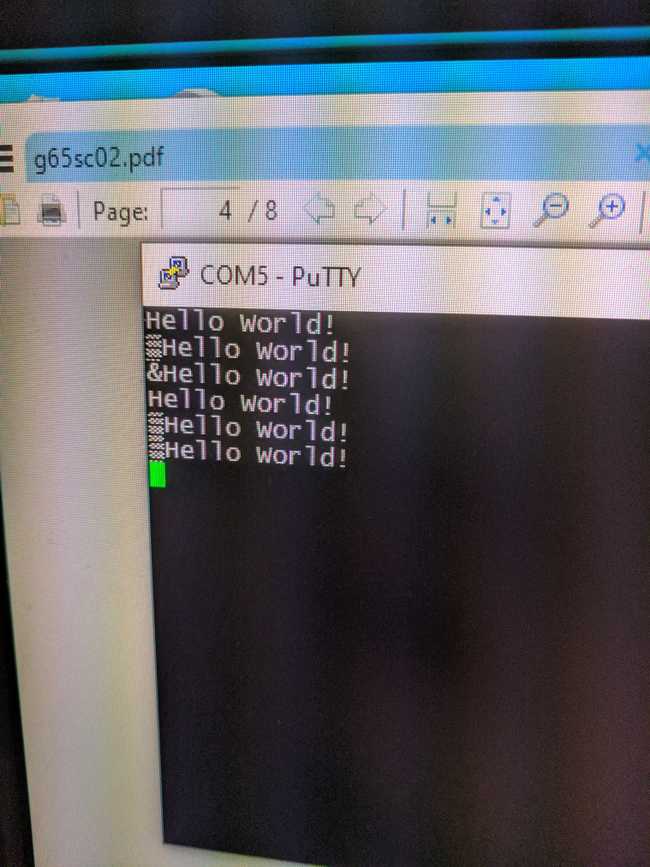

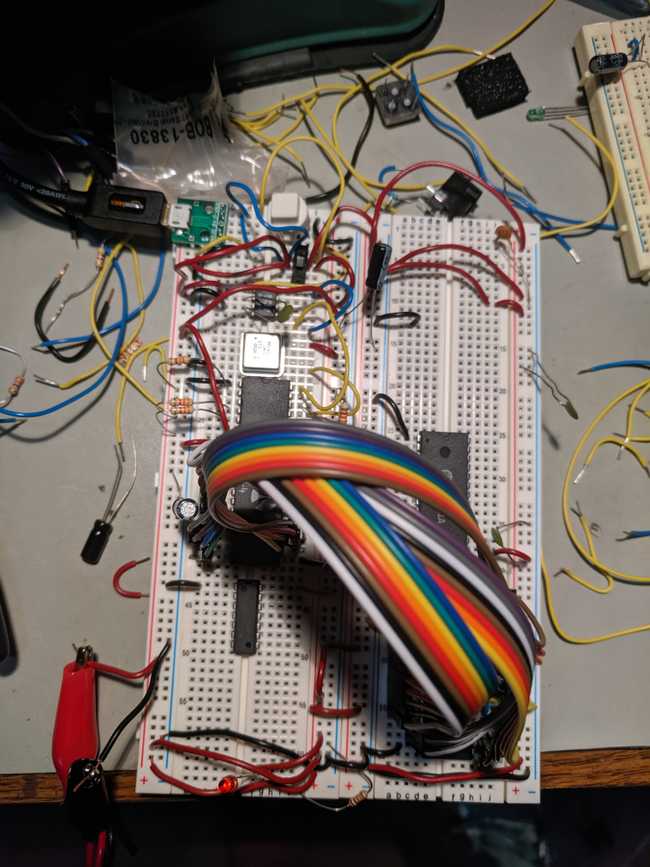

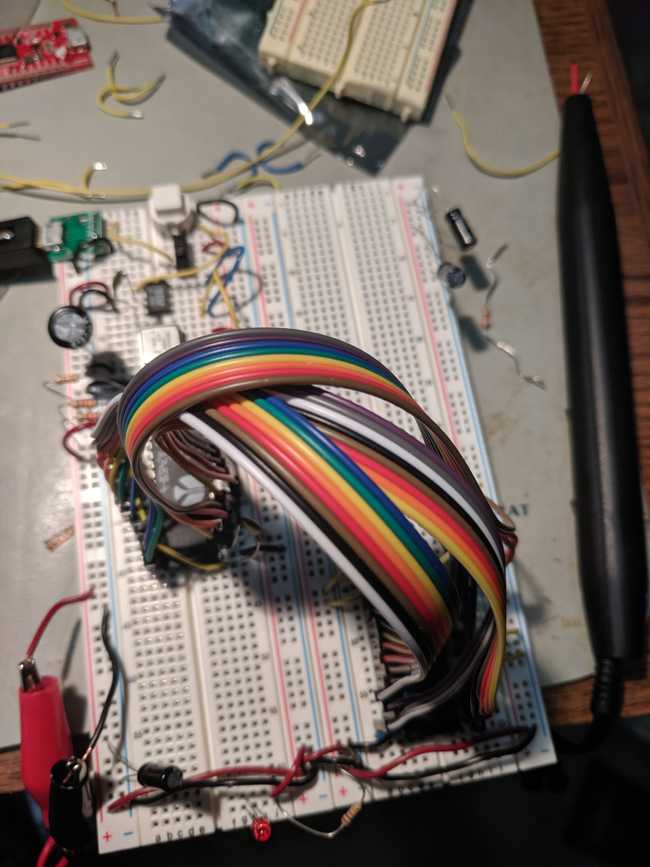

Eventually, early in 2019, there was a hack day and, since my past experiences with hack days have frequently left a bad taste in my mouth, I decided that I’d support the idea of doing a hack day by doing something completely useless… A 6502 breadboard computer.

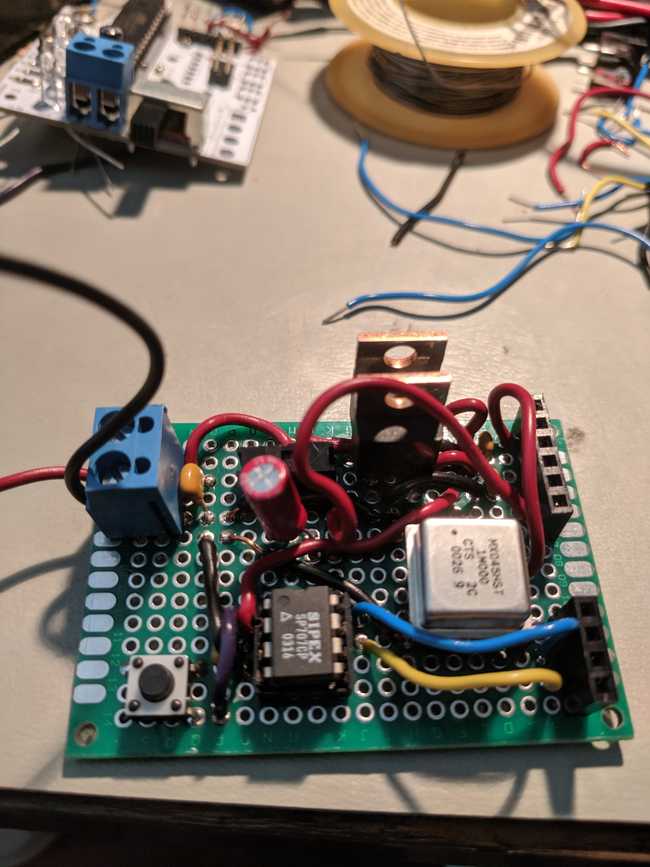

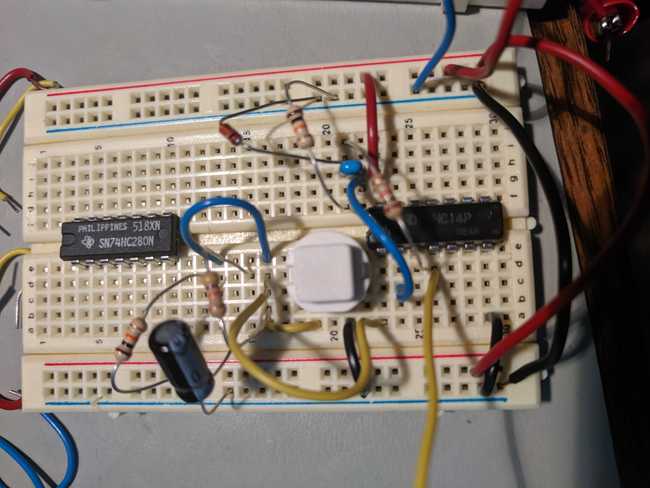

I was mostly inspired by Dirk Grappendorf’s really quite nice 6502 build, especially how he provided a nice suite of test firmware, so a lot of my design is inspired by that build or Daryl’s SBC2.

I ran into some problems, learned some hard lessons about breadboarding, and kept going after the hack day.

GitHub repo